Mid-century Outlook

By mid-century, more winter precipitation will fall as rain rather than snow, lessening April snowpack. Photo: Kevin Hyde.

Climate

Climate

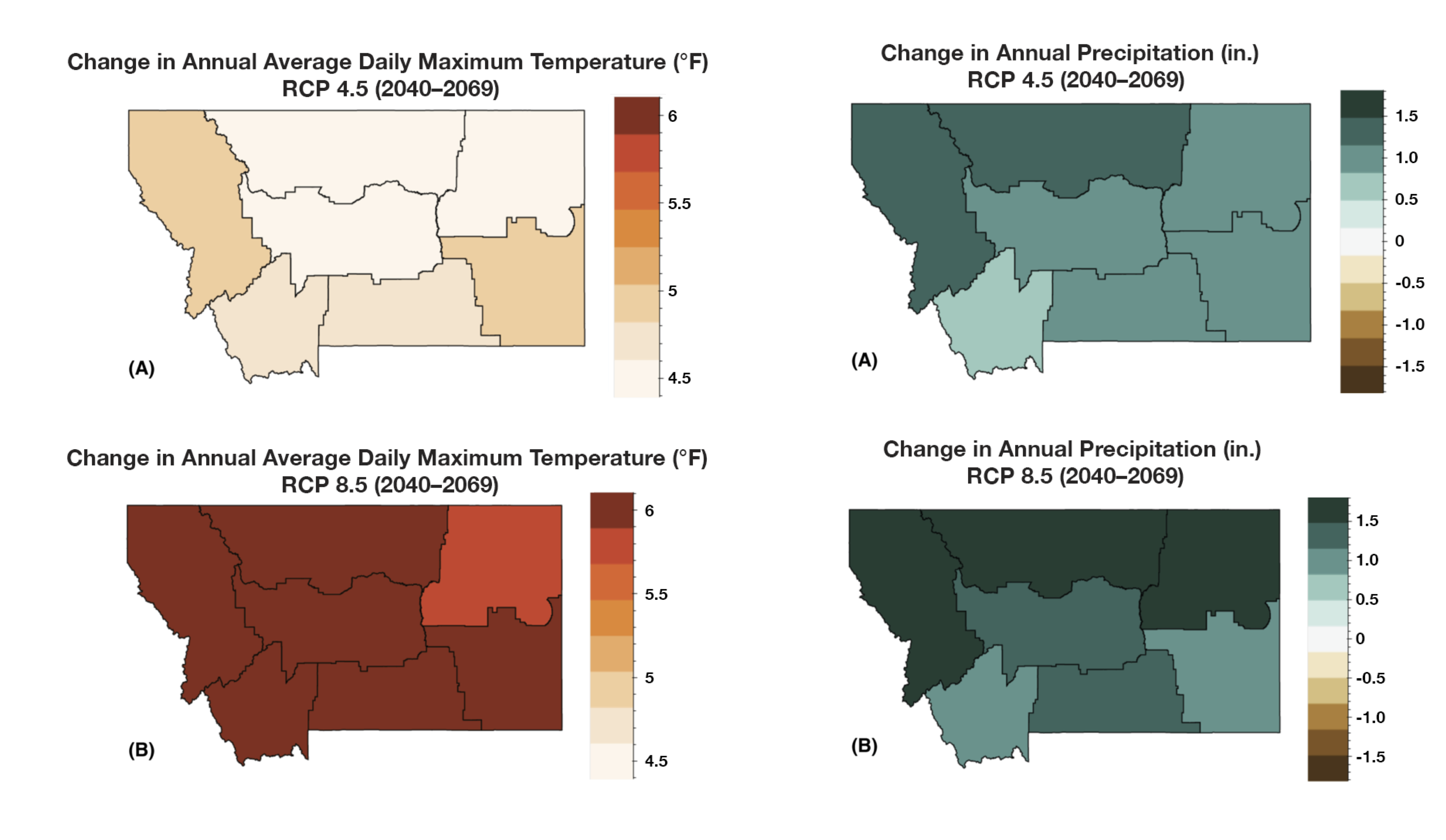

Agriculture is an incredibly important part of Montana’s culture, economy, and landscape, and an industry that is directly impacted by changes in temperature, precipitation, and extreme weather events. Each fall, we provide information about how environmental conditions in Montana are projected to change over the next 30 years. We realize that agricultural operations in Montana are diverse and that each producer will need to respond differently to changing conditions. Below, we provide information from the Montana Climate Assessment (MCA), an effort to synthesize, evaluate, and share credible and relevant scientific information about how our climate is changing in Montana, produced by Montana State University and the University of Montana. This is only a summary of the MCA — visit MontanaClimate.org for more details on changes in your region.

Climate basics

Climate is driven largely by energy from the sun, and how it is reflected, absorbed, transformed (as in photosynthesis), or re-radiated (as heat). Each of these processes influences climate through changes to temperature, the hydrologic cycle, vegetation, and atmospheric and ocean circulation patterns. A changing climate encompasses both increases and decreases in temperature, as well as shifts in precipitation, changing the risk of certain types of severe weather events, and altering other features of the climate system.

Montana’s unique features

To understand how a changing climate is impacting Montana, we must first understand Montana’s unique geography. Montana is the fourth largest state in the nation and its location within North America exposes the state to a mix of diverse weather systems that originate from the Pacific Ocean, the Arctic, and sometimes subtropical regions. The Continental Divide, which has a predominantly north-south alignment in Montana, effectively splits the state into climatically distinct western wet and eastern dry regions with respect to moisture from eastward-flowing Pacific Maritime air. The state also includes the headwaters of three major river basins—the Missouri, Snake/Columbia, and Saskatchewan — two of which encompass almost one-third of the landmass of the conterminous United States. Consequently, Montana’s climate influences the water supply of a large portion of the country, and its water supports communities, ecosystems, and economies far beyond its borders.

Montana’s unique geography means that climate varies across the state, as it does across the nation. The Montana Climate Assessment aggregates past climate trends and future climate projections into seven Montana climate divisions. These seven climate divisions are a subset of the 344 divisions defined by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) based on a combination of climatic, political, agricultural, and watershed boundaries.

How are temperature and precipitation changing in Montana?

Temperature and precipitation are already changing in Montana and are projected to change more in the future. More specifically, annual average temperatures have been increasing since 1950. While annual average precipitation has remained steady, we are seeing important seasonal changes, including the trends listed below. It is important to note that we don’t necessarily see these impacts every year, but over time (on average) they are becoming more common.

- More winter precipitation falling as rain instead of snow.

- Lower levels of snowpack.

- Earlier snowmelt in the spring leading to earlier peak runoff and flooding.

- Lower mid-late summer streamflow (as a result of earlier snowmelt and runoff, and more evaporation due to higher summer temperatures).

- Soils drying out earlier due to higher summer temperatures and increased evapotranspiration.

- More variability year-to-year because of changes in inter-annual and decadal climate patterns.

- A longer growing season, which could be beneficial if there is enough moisture for plants.

These trends are expected to intensify as we move toward the middle of the century.

The Montana Climate Assessment outlines the following changes to temperature and precipitation. Each point is followed by an expression of confidence. For more information, see the Climate chapter of the Montana Climate Assessment.

- Annual average temperatures, including daily minimums, maximums, and averages, have risen across the state between 1950 and 2015. The increases range between 2.0–3.0°F during this period. [high agreement, robust evidence]

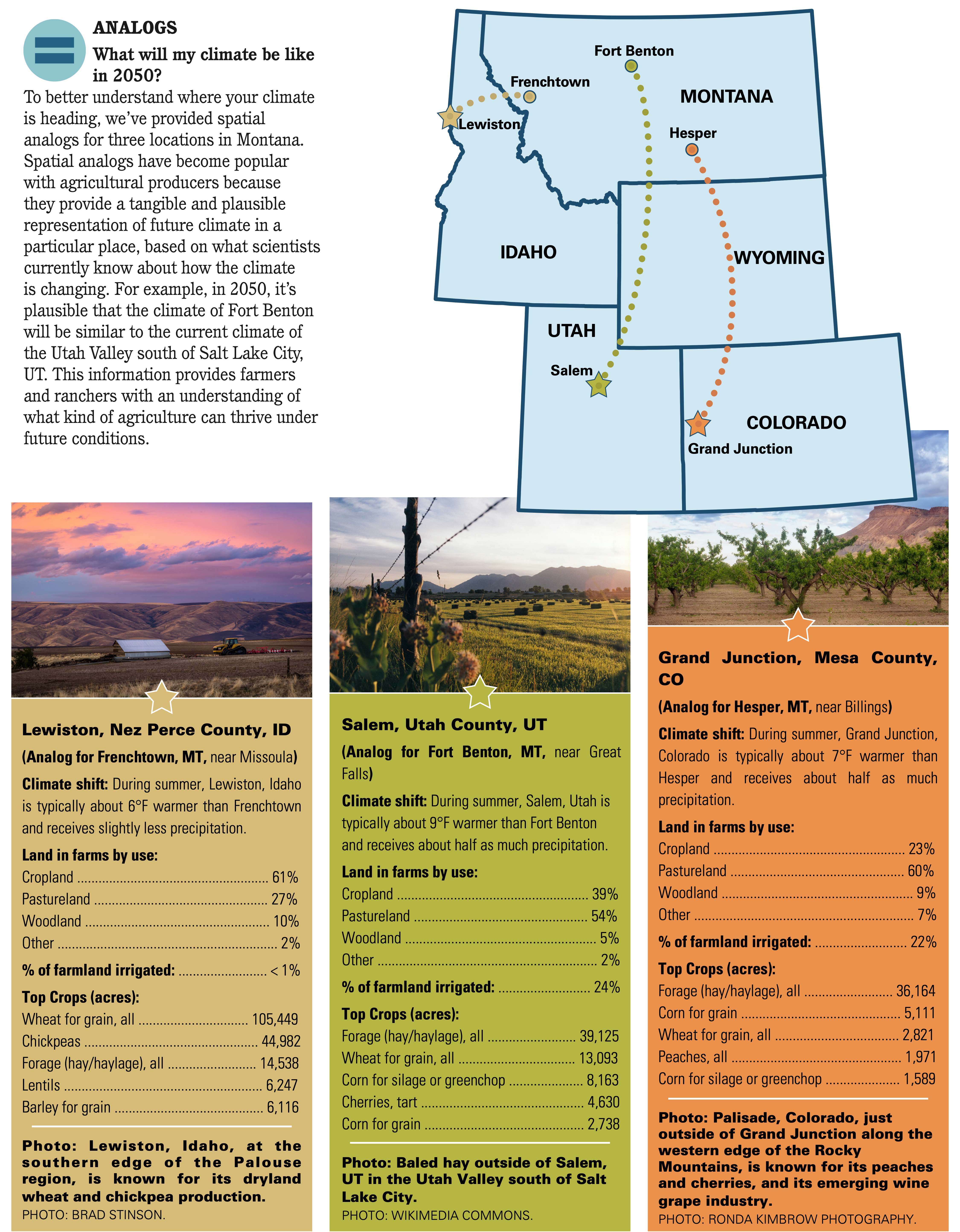

- Montana is projected to continue to warm in all geographic locations, seasons, and under all emission scenarios throughout the 21st century. By mid-century, Montana temperatures are projected to increase by approximately 4.5–6.0°F, in addition to the 2-3°F warming we have already seen. These state-level changes are larger than the average changes projected globally and nationally. [high agreement, robust evidence]

- Despite no changes in average annual precipitation between 1950 and 2015, there have been changes in average seasonal precipitation over the same period. Average winter precipitation decreased by 0.9 inches, which can largely be attributed to natural variability and an increase in El Niño events, especially in the western and central parts of the state. A significant increase in spring precipitation (1.3–2.0 inches) also occurred during this period for the eastern part of the state. [moderate agreement, robust evidence]

- Across the state, precipitation is projected to increase in winter, spring, and fall; precipitation is projected to decrease in summer. The largest increases in precipitation are expected to occur during spring in the southern part of the state. The largest decreases in precipitation are expected to occur during summer in the central and southern parts of the state. [moderate agreement, moderate evidence]

The maps above show the projected increase in annual average daily maximum temperature (°F) and annual total precipitation (inches) for each climate division in Montana for the periods 2040–2069. Because of uncertainties related to how technology, economics, and policy will influence carbon emissions in the future, the Montana Climate Assessment utilizes two scenarios (RCP 4.5 where carbon emissions peak around 2040 and then decline, and RCP 8.5 where carbon emissions continue to increase through the 21st century). Under both scenarios Montana is projected to be much warmer in the future.

Agriculture

Agriculture

Agriculture is a key industry in Montana, generating over $3.5 billion in 2017 through the sale of agricultural commodities (USDA NASS 2017). Montana agriculture includes a mosaic of dryland and irrigated agriculture, commodity and specialty cropland, and native and planted rangeland. Farms and ranches in the state contribute to feeding the country and the world, provide important open space and wildlife habitat, and support rural communities and the Montana economy.

Montana agricultural producers have long contended with changes in climate and weather, including extreme events and climate variability. The changes outlined above impact all aspects of Montana agriculture, from rangeland productivity and crop yields to disease, pests, and weeds. However, predictions about the exact ways that climate will impact agricultural producers are difficult, because every operation is different and there are many uncertainties related to climate projections, commodity prices and the cost of inputs, available technology and insurance, among others. Each producer knows their land and operation and is best positioned to understand how current and future changes will affect them.

Here are some of the projections about impacts to Montana agriculture. Each point is followed by an expression of confidence in that message. For more information, see the Agriculture chapter of the Montana Climate Assessment.

- Decreasing mountain snowpack will continue to lead to decreased streamflow and less reliable irrigation capacity during the mid-late summer. Reduced irrigation capacity will have the greatest impact on hay, sugar beet, malt barley, market garden, and potato production across the state. [high agreement, robust evidence]

- Increases in temperature will allow winter annual weeds, such as cheatgrass, to increase in distribution and frequency in winter wheat cropland and rangeland. Their spread will result in decreased crop yields and forage productivity as well as increased rangeland wildfire frequency. [high agreement, medium evidence]

- Changes in other parts of the world will impact the price of commodity crops, such as small grains, that are more directly driven by global markets. Crops that are more directly tied to local markets or specialized non-local markets may not be impacted as much by impacts to agriculture in other parts of the world. [high agreement, medium evidence]

Increasing resilience in the face of change

Social and economic resilience to withstand and adapt to variable conditions has always been a hallmark of Montana farmers’ and livestock producers’ strategies for coping with climate variability. Producers build resilience in different ways, depending on their operations and their goals. Diversified cropping systems, including rotation with pulse crops and innovations in tillage and cover-cropping, along with other measures to improve soil health, may enable producers to adapt to the changes described here.

Resources for producers can be found online at the USDA Northwest Climate Hub, the USDA Northern Plains Climate Hub, the Natural Resources Conservation Service, USDA Farm Service Agency, and Montana State University Extension.

Analogs

Analogs