Mid-century Outlook

A peach orchard near Grand Junction, Colorado. By midcentury, portions of eastern Montana may feel like western Colorado. Photo: Ronda Kimbrow Photography.

Climate

Climate

Agriculture is an incredibly important part of Montana’s culture, economy, and landscape, and an industry that is directly impacted by changes in temperature, precipitation, and extreme weather events. Each fall, we provide information about how climatic conditions in Montana are projected to change over the next 30 years. We realize that agricultural operations in Montana are diverse and that each producer will need to respond differently to changing conditions. Below, we provide summary information from the Montana Climate Assessment (MCA), an effort to synthesize, evaluate, and share credible and relevant scientific information about how our climate is changing in Montana, produced by Montana State University and the University of Montana. This is only a summary of the MCA — visit MontanaClimate.org for more details on changes in your region.

The Montana Climate Assessment outlines the following changes to temperature and precipitation. Each point is followed by an expression of confidence. For more information, see the Climate chapter of the Montana Climate Assessment.

- Annual average temperatures, including daily minimums, maximums, and averages, have risen across the state between 1950 and 2015. The increases range between 2.0–3.0°F during this period. [high agreement, robust evidence]

- Montana is projected to continue to warm in all geographic locations, seasons, and under all emission scenarios throughout the 21st century. By mid-century, Montana temperatures are projected to increase by approximately 4.5–6.0°F, in addition to the 2–3°F warming we have already seen. These state-level changes are larger than the average changes projected globally and nationally. [high agreement, robust evidence]

- Despite no changes in average annual precipitation between 1950 and 2015, there have been changes in average seasonal precipitation over the same period. Average winter precipitation decreased by 0.9 inches, which can largely be attributed to natural variability and an increase in El Niño events, especially in the western and central parts of the state. A significant increase in spring precipitation (1.3–2.0 inches) also occurred during this period for the eastern part of the state. [moderate agreement, robust evidence]

- Across the state, precipitation is projected to increase in winter, spring, and fall; precipitation is projected to decrease in summer. The largest increases in precipitation are expected to occur during spring in the southern part of the state. The largest decreases in precipitation are expected to occur during summer in the central and southern parts of the state. [moderate agreement, moderate evidence]

Agriculture

Agriculture

Montana agricultural producers have long contended with changes in climate and weather, including extreme events and climate variability. The changes impact all aspects of Montana agriculture, from rangeland productivity and crop yields to disease, pests, and weeds. However, predictions about the exact ways that climate will impact agricultural producers are difficult, because every operation is different and there are many uncertainties related to climate projections, commodity prices and the cost of inputs, available technology, and insurance, among others. Each producer knows their land and operation and is best positioned to understand how current and future changes will affect them.

Here are some of the projections about impacts to Montana agriculture. Each point is followed by an expression of confidence in that message. For more information, see the Agriculture chapter of the Montana Climate Assessment.

- Decreasing mountain snowpack will continue to lead to decreased streamflow and less reliable irrigation capacity during the mid-late summer. Reduced irrigation capacity will have the greatest impact on hay, sugar beet, malt barley, market garden, and potato production across the state. [high agreement, robust evidence]

- Increases in temperature will allow winter annual weeds, such as cheatgrass, to increase in distribution and frequency in winter wheat cropland and rangeland. Their spread will result in decreased crop yields and forage productivity as well as increased rangeland wildfire frequency. [high agreement, medium evidence]

- Changes in other parts of the world will impact the price of commodity crops, such as small grains, that are more directly driven by global markets. Crops that are more directly tied to local markets or specialized non-local markets may not be impacted as much by impacts to agriculture in other parts of the world. [high agreement, medium evidence]

Increasing resilience in the face of change

Social and economic resilience to withstand and adapt to variable conditions has always been a hallmark of Montana farmers’ and livestock producers’ strategies for coping with climate variability. Producers build resilience in different ways, depending on their operations and their goals. Diversified cropping systems, including rotation with pulse crops and innovations in tillage and cover-cropping, along with other measures to improve soil health, may enable producers to adapt to the changes described here.

Resources for producers can be found online at the USDA Northwest Climate Hub, the USDA Northern Plains Climate Hub, the Natural Resources Conservation Service, USDA Farm Service Agency, and Montana State University Extension.

Planning for the Future

The analogs presented in the next section reflect uncertainty regarding future greenhouse gas emissions and the severity of climate change. In short, scientists know that things are changing and we often know the direction of the change (for example, warmer and drier), but we can’t predict exactly what your climate will look like in 2050. Also, the year 2050 is pretty far off in the future and your long-term planning might be focused on the next 5–10 years. So how do you plan for the future? Here’s what your fellow farmers and ranchers have told us in response to this question:

- As you observe what’s happening on your farm or ranch, think about what changes you will need to make to your operation as things continue to shift. What would you need to do if there is more prolonged drought? Make a plan and think about when you need to start transitioning to new practices.

- Montana farmers and ranchers often tell us how risky it is to transition to new crops or management practices. Watch what’s working for your neighbors who are experimenting with new practices. Talk with the Agricultural Research Center in your region. Take a small patch and try something new to see how it works as conditions change.

- Build in flexibility and diversity as much as you can. Diversify your operation so you have multiple income streams. Experiment in ways that require small investments and are easy to reverse if they don’t work out.

Analogs

Analogs

What might my climate be like in 2050?

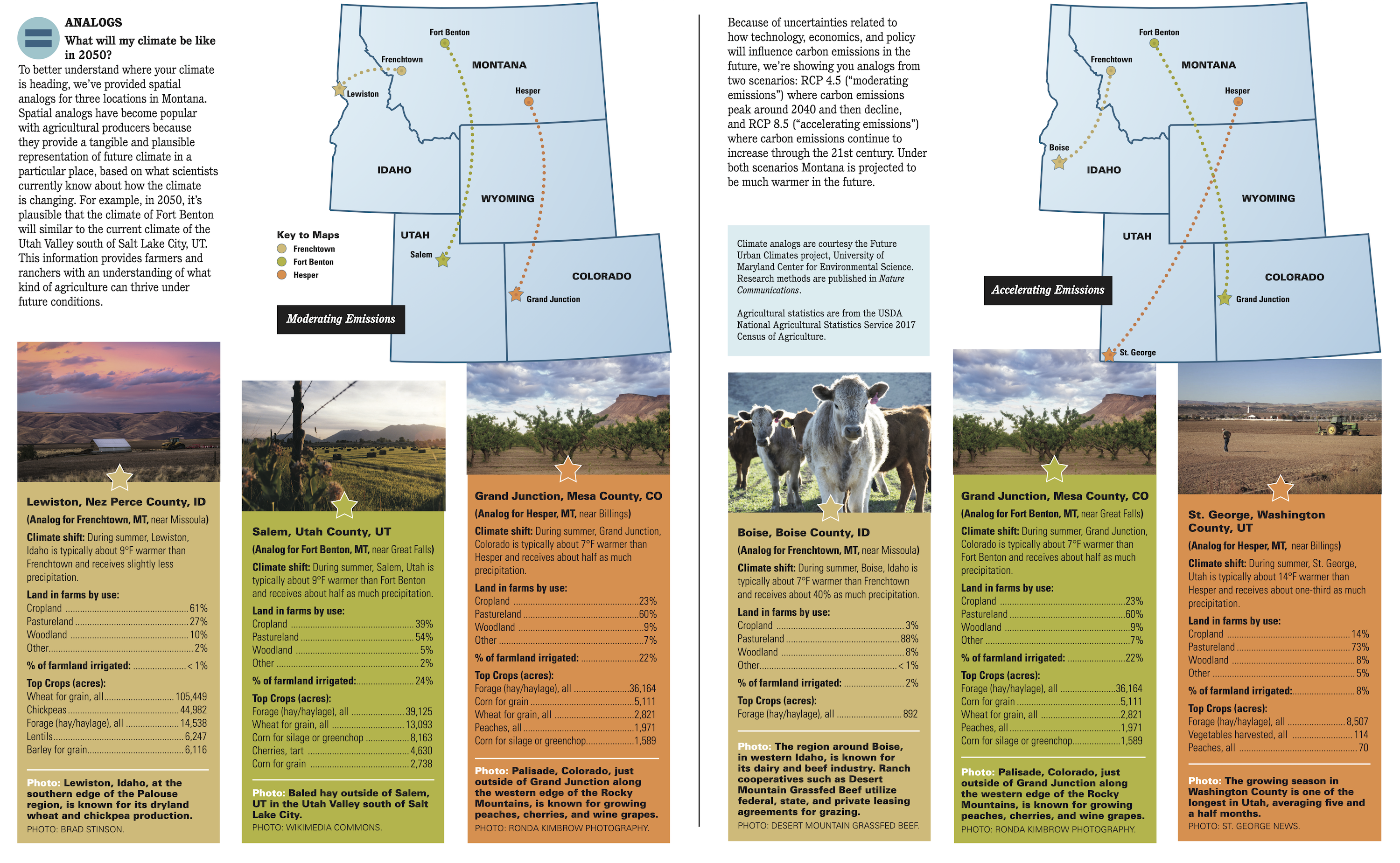

To better understand where your climate is heading, we’ve provided spatial analogs for three locations in Montana. Spatial analogs have become popular with agricultural producers because they provide a tangible and plausible representation of future climate in a particular place, based on what scientists currently know about how the climate is changing. For example, in 2050, it’s plausible that the climate of Fort Benton will similar to the current climate of the Utah Valley south of Salt Lake City, UT. This information provides farmers and ranchers with an understanding of what kind of agriculture can thrive under future conditions.

Because of uncertainties related to how technology, economics, and policy will influence carbon emissions in the future, the we’re showing you analogs from two scenarios: RCP 4.5 (“moderating emissions”) where carbon emissions peak around 2040 and then decline, and RCP 8.5 (“accelerating emissions”) where carbon emissions continue to increase through the 21st century. Under both scenarios Montana is projected to be much warmer in the future.

Climate analogs are courtesy the Future Urban Climates project, University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science. Research methods are published in Nature Communications.

Agricultural statistics are from the USDA National Agricultural Statistics Service 2017 Census of Agriculture.